The Wind Rises: Dreams, Detail, and the Weight of Quiet Ambition

Don’t ask me why they spoke in french, I also am confused, but I let it slide because it's lowkey valid

I’ve needed a space to articulate my own loneliness not at the level of state, or nation, or race or place

— Moses Sumney, Live from Blackalachia

The Wind Rises came to me at the right time. When I watched it, I had already spent half the day thinking more and more about the shortness of time, it’s fleeting nature as the one currency we cannot work for, cannot earn. The only currency it is legal, and widely acceptable, to be robbed of.

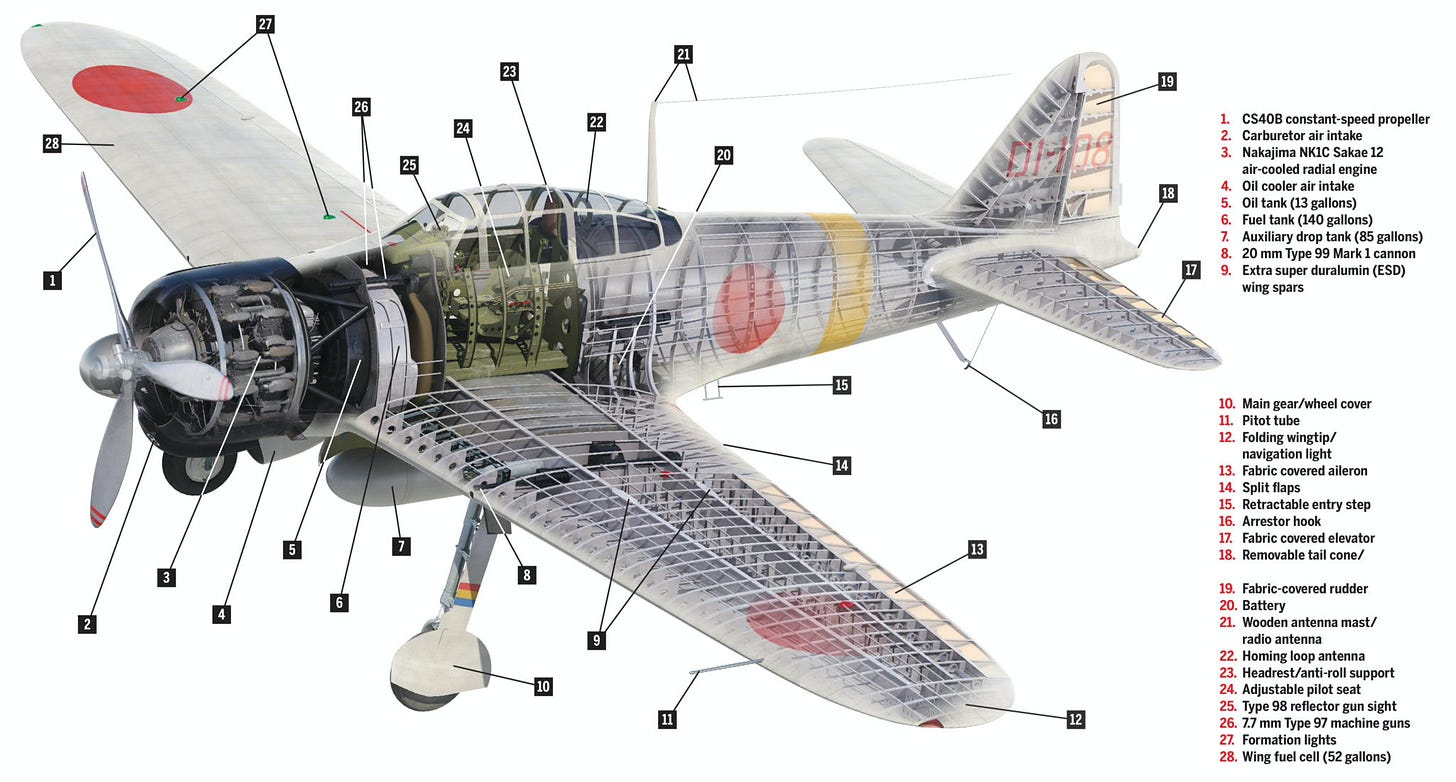

The film is loosely based on Tatsuo Hori’s 1936 romantic fiction novel of the same name. It also incorporates events from the life of Jiro Horikoshi, the inventor of the A6M Zero fighter plane.

The film is set amidst the back drop of the looming second world war, where the old and the new are meeting together in a flurry of political instability, western influence is creeping into Japan, who stands on a brink of birthing a new norm. We see it in the dress of the characters who change in and out of more traditional dress to dandy suits and streets filled with modern cars as well as older carts carried by cattle. Jiro and a friend come upon a field of oxen, and the friend exclaims that the oxen are used to take the plane prototypes from warehouses to the airstrip where they will be tested- the quiet recognition that the flesh machines of old will usher in the metal husks of new is stated regretfully, as the characters regard the oxen as ‘archaic’ such small detail encapsulates the mindset of Jiro and his team, and on a wider level Japan in the 1920’s-1930’s desperately trying to be regarded on the global scale but set back due to lack of technological advancement.

One of the first images we see of Jiro are his eyes — framed by thick glasses, constantly observing. It’s a quiet signal: he’s someone cultivating a distinct way of seeing the world, someone crafting his own method of moving through difficulty, breaking out of the inferiority complex that other characters tend to have when comparing their developements to that of teh western world.

Jiro is nearsighted, unable to see things far away — and yet this is presented as his strength. His attention to detail defines him. His myopia, literal and metaphorical, asks us to reconsider what it means to see clearly. These days, when I’m so often swallowed by fear of an uncertain future, Jiro reminds me that clarity is sometimes found not in looking ahead, but in looking closely. He pays attention to what’s near, to what’s real, even when it hurts. Maybe especially when it hurts. He doesn’t shy away from difficulty. He doesn’t dramatise it, either.

Challenges are approached as necessary work — something to be sat with, studied, respected. I just realised — curiosity is a five-syllable word. Jiro embodies the word wholly, slowly and with care. Each syllable like a step in the process, each step needing time.

He dreams, and beyond the escapisim of Jiro’s dreams he also allows himself time to reflect. His failures don’t humiliate him; they teach him. There’s that moment with Caproni — the Italian aviation maestro who visits him in dreams — refuses to have a failed test flight recorded. The difference is stark. Where others conceal their failures, Jiro learns from his. That alone sets him apart.

His dedication to craft is not driven by ego or personal glory. What he builds will be used in war. He knows this. And he doesn’t turn away from the weight of that knowledge. He continues, quietly. Trapped in a reality where politics and ethics bleed into invention. His dream is peace, but his neutrality isn’t enough. In moments like these, when decisions are made without you, neutrality becomes complicity. And still, he dreams.

Destruction has never looked as beautiful as it does in The Wind Rises. Earthquakes ripple through the ground like waves through a bouncy castle. The flames feel almost friendly. The sounds — snapping engines, shifting gears — all feel alive. We watch physics in action through Jiro’s eyes. Every frame transmits motion the way he understands it: dress hems catching the wind, smoke billowing just so, snow bursting in the air. I might be exaggerating the detail, but it’s all so beautifully done. I’m watching a scene now where an engine starts up and the sound design layers voices like a quartet warming up — it’s haunting and lovely.

“Dead to the world, with a face that looks like it’s carrying the future of the Japanese revolution.”

— Jiro’s friend, as he sleeps.

The European portrayal is quite interesting in this movie. Caproni the Italian maestro who shows up in his dreams to inspire him speaks with that irritating altruism that verges on micro agression in my opinion “Little Japanese boy with bad eyes, you can do anything you put your mind to”- not a direct quote but it reminds me of the line in To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything “Little latin boy in drag, why are you crying?”. Caproni makes crafts that are beautiful, intended for peace yet ultimately destined for war, Caproni is portrayed as this homely little man, speaking of, I love how Jiro grows up and is taller than Caproni in the end of the film, details. While he is encouraged by his italian sleep paralysis mentor to dream big and take inspiration from wherever, this is juxtaposed against the German stinginess and worry that the Japanese will ‘copy’ everything, you can be inspired but not aspire to be better than. It’s a reminder that Jiro and his crew are on a time crunch, and that the world was very much at war.

The writers had an excellent understanding of being a foreigner and dealing with the inherent stereotypes that you unknowingly adopt on strange land, it's always interesting but saddening when you’re watching something and remember that institutional racism exists :( and you have to lock back in to the struggle to dismantle systems of white supremacy. I enjoyed this theme particularly due to its closeness to my heart, and although interesting how Jiro’s western influences in dreams and real life are uncannily kind to him, the film somewhat errs on that standpoint. I’m so tired of the idea that good white people in high places will be magnanimous and philanthropic, at a time that is all too convenient, it doesn’t work that way (can someone say reparations now?)

And then there’s the romance. It's refreshing — soft, sincere, and almost juvenile in the best way. Nahoko sees Jiro as knightly, and there's a sweetness in how their feelings land at the same time. I love that: mutual love, maintained with care from both sides. No one gets to slack. And while it’s technically a romantic film, I appreciate that love isn’t plastered across every scene. This is my third time watching, and honestly, love wasn’t what I was paying attention to this time — and that’s okay. The film gives you space.

At the end of the movie, I had already shed my fair share of tears as Jiro's lover urges him to live, my lover is sleeping peacefully next to me, quiet breaths grounding me, warmth keeping the cold uncertainty at bay. We were going for ‘feel good’ movie with light themes, so we didn’t hit the mark. I knew I should’ve insisted on the care bears movie, but we live and we learn.

Things this film inspired me to do:

Spend more time sleeping and dreaming

Learn about planes, especially the kinds used in Nigerian aviation.

Get good at identifying planes by sight

Love those the wind brings my way

Persevere…queersevere dare i say

A LEGEND REVEALED: THE MITSUBISHI A6M2 ‘ZERO’